Leopoldo Méndez

“I am black, a woman, a sculptor, and a printmaker. I am also married, the mother of three sons, and the grandmother of five little girls (now seven girls and one boy) […] all of these states of being have influenced my work and made it what you see today.”

– elizabeth catlett

Collaborative processes have a rich tradition in Mexico, and one of the initiatives whose imprint is widespread is that of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (People’s Graphic Workshop), better known as the TGP, which dates back to 1937. Several of the founding members came from another group called the Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists). Reverberating precepts promoted by Muralism, they continued to encourage visual production committed to struggles and social justice, denouncing situations in which peasants and workers lived, and especially resisting and questioning messages, effects or practices linked to prevailing fascism.

The TGP’s graphics – in the spirit of agitation and propaganda – also circulated through posters, flyers, and calendars, appealed to a visual militancy and also to a critique of production models focused on the individual artist.

The TGP promoted instead organizational resources of a collective nature through meetings and assemblies, as can be seen in the photographs. In them they discussed what to represent, how to form the group of volunteers who would produce the image, taking care that the agent in charge was recognized, and at the same time, the collective exercise through the TGP’s distinctive seal/logo.

In March 1938 the TGP approved a document which contained its interests and objectives, a kind of manifesto or statement in which they agreed to work in lithography, metal and wood printmaking and linoleum.

This workshop is created in order to stimulate the production graph in order to benefit the interests of the people of Mexico, and for that objective is proposed to bring together the largest number of artists through the method of collective production.

Although this document was not published, years later, in March 1945, they published their

Declaration of Principles in which they reaffirmed themselves as a center of collective work for functional promotion, as well as their vision of art at the service of the people, so that their production should reflect the social realities of their time.

Like other collective strategies over time, the TGP had various moments of cohesion and internal tension, its participants varied in number and geographical origin at different times. Among its members were artists such as Leopoldo Méndez, Pablo O’Higgins, Luis Arenal and Adolfo Mexiac, also had an important participation of women artists such as Mariana Yampolski, Rini Templeton, Elizabeth Catlett and Margaret Taylor, whose work, in the context of the new feminisms and the depatriarchalizing of history, is being revalued and situated.

Given the great artistic performance and the profuse political activity of the TGP, various foreign artists (mainly American) temporarily joined the workshop to contribute their work to the production of socio-political prints; these artists were called guest artists and some of them were: John Wilson, Hannes Meyer, Lena Bergner, Charles White, Eleanor Coen, Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs, Rini Templeton, Elizabeth Catlett, among others. These links consolidated the international character of the TGP and in a way stimulated the development of other related projects such as Workshops of Graphic Art in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York.

Regarding the participation of the Mexican artist Leopoldo Méndez, considered one of the most important Mexican engravers, a social and collective perspective was reflected in the productions he made for various organizations such as the League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists, the Mexican Communist Party, the Popular Socialist Party of Mexico and the Confederation of Latin American Workers. Méndez’s artistic production took shape when he joined the Estridentismo movement, and his work promoted leftist and post-revolutionary ideals that allowed him to generate a broad visual vocabulary linked to the socio-political history of Mexico, but also to criticize and denounce the violence promoted by fascist projects in Europe.

These works – which are pioneering for the conformation of other subjectivities – far from operating on an exclusively retinal level, contributed to the insertion of other subjects of representation continually reviled in the tradition of artistic representation or, alternatively, repositioned and framed them in a dignified way and in another aesthetic-political-symbolic order that we can read today from a proto-decolonial perspective.

The validity of the TGP – in a present where rights are disputed, new turns of violence exist and where artistic production can go through the crossroads of art/politics thanks to graphic – asks us not only to reflect but also to permanently sustain points, representations and frameworks that incite us to read critically in and from the present.

getsemaní guevara and sol henaro

translated from Spanish by ana laura borro

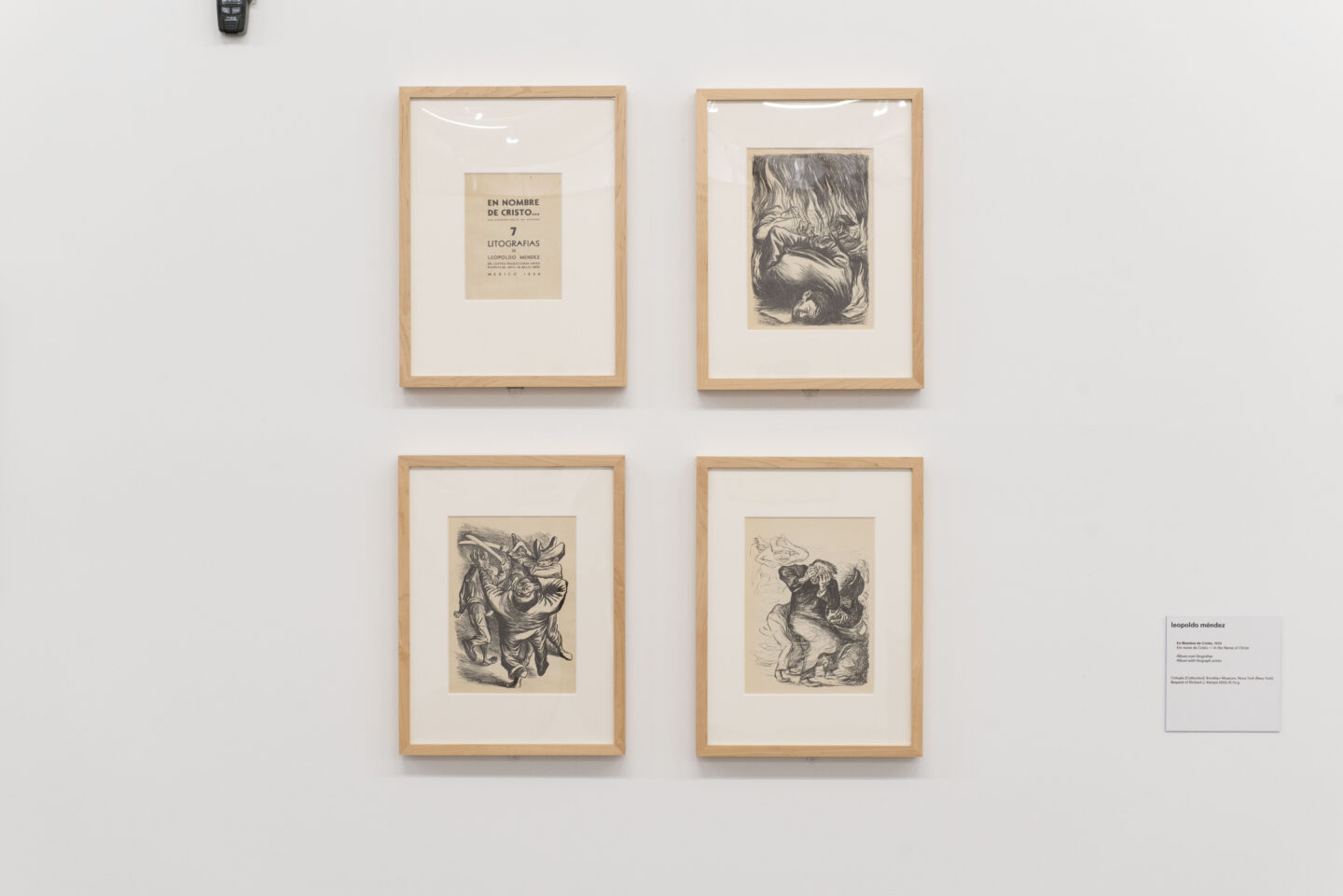

Leopoldo Méndez (Mexico City, Mexico, 1902 – 1969) was an artist and engraver. He directed the Oficina Gráfica Popular from 1937 to 1952. Méndez was a member of the Mexican Communist Party and believed that art should be used as a weapon for social movements. His work addresses themes such as the Mexican Revolution, the Cristero War, fascism in Europe, socialist education, the labor movement, and the injustices caused by capitalism.

- Vista de obras de Leopoldo Méndez durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Leopoldo Méndez durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Leopoldo Méndez durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Leopoldo Méndez durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Leopoldo Méndez durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Leopoldo Méndez durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

Português

Português