Jesús Ruiz Durand

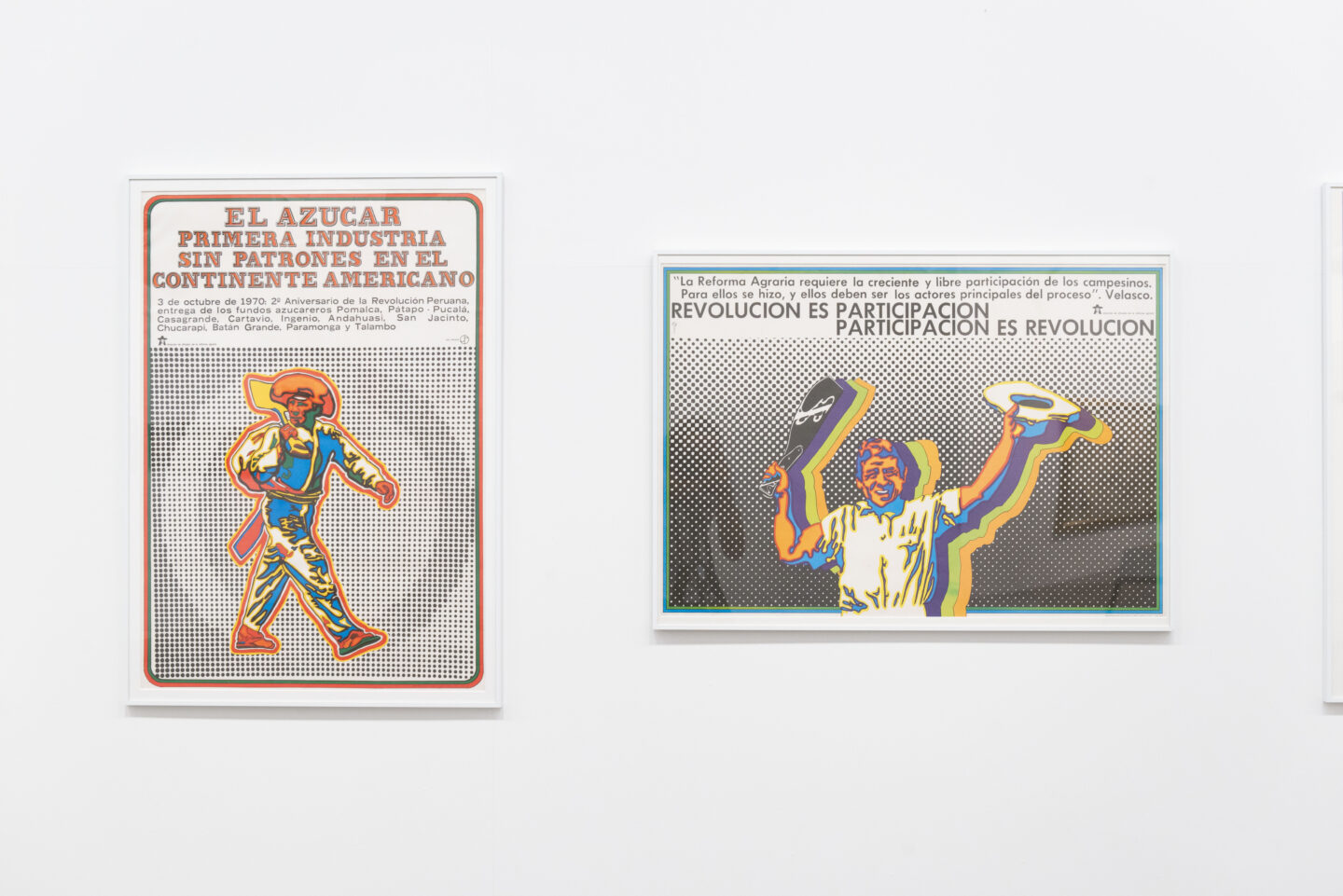

Between 1969–1974, Jesús Ruiz Durand produced a series of posters to publicize the Agrarian Reform initiated by the government of General Velasco Alvarado in Peru. Under the notion of pop achorado – an expression that means “rebellious, insolent, indignant, belligerent, vulgar, choleric, insurgent, insubordinate” – this graphic style took the pulse of an Indigenous population that broke up with the slavish submission that, for centuries, had made the Peruvian plantation and the relationship between the pongos and the gamonales¹ a hotbed of cruelty.

Through his work for the Land Reform Promotion and Diffusion Direction, Ruiz Durand travelled around the country, photographing and talking to Quechua-speaking peasants who were recovering lands. He developed a technique that consisted of fragmenting the image through a process of solarization (or sabattier effect), distributing flat colours by areas, reframing them like comic strips and printing them in offset in CMYK process. Experimenting with dots and patterns, he invested an outline of phosphorescence, vitality and optimism to the Indigenous bodies that seemed to set foot outside the waiting room of history, incinerating the symbolic and material bases of servitude and dispossession in Peru.

Styling an old illustration from school books of the face of Tupac Amaru II, Ruiz Durand designed the logo of the Agrarian Reform, which was the central figure in two posters, one yellow and the other blue. Eclipsing the silhouette from the front and in profile, inserting it into geometric compositions and optical and chromatic reverberations, Ruiz Durand made the face of one of the leaders of the fiercest Andean insurgency of the eighteenth “century against the Spanish invasion more dynamic, giving it a vibrant physiognomy that could mutate, multiply and light up, through superimpositions and lighting effects. Through a kinetic formal synthesis, he synchronized the anti-colonial messianism of Tupac Amaru II with the revolution in progress.

But in the undulating and yellowish contours that envelop the peasant bodies holding tools or working the land, it is also possible to see the light of the eclipses, under which the inhabitants of the altiplano “walk full of foreboding,” as Arguedas writes. The Agrarian Reform, as a continuation of the anti-colonial war by other means, was and is an instant of danger. This flickering light anticipated, in its shadows, the murmur of violence that would come just a few years later, with the internal war between the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso) and the Peruvian state. It retains the endless rage of the pongo, “that rage that burns in the seed of his heart, like a fire that will not go out.”²

fernanda carvajal

translated from Spanish by ana laura borro

Jesús Ruiz Durand (Huancavelica, Peru, 1940. Lives in Lima, Peru) is a mathematician, painter, printmaker, and graphic designer. He studied painting at the School of Fine Arts of Peru and animation filmmaking at New York University. He is a professor of electronic design, contemporary aesthetics, and cultural studies. His kinetic work is part of public collections, such as the MoMA (New York, USA) and the Hermitage Museum (Moscow, Russia).

1. Pongos were the peasants and Indigenousindigenous people who worked as servants on the plantations in Peru and gamonales were mainly landowners from the highlands, who exploited the labour power of the pongos in a regime of serfdom, very similar to the feudal form [NT].

2. José María Arguedas, “Carta a Hugo Blanco-1969”, in Hugo Blanco (ed.), La verdadera historia de la Reforma Agraria. Lima: Ediciones Lucha Indígena, 2009.

- Vista de obras de Jesús Ruiz Durand durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Jesús Ruiz Durand durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

- Vista de obras de Jesús Ruiz Durand durante a 35ª Bienal de São Paulo – coreografias do impossível © Levi Fanan / Fundação Bienal de São Paulo

Português

Português